this year, i began to experiment with creating simple text “etudes.” initially, i thought of them as memory aids. writing them helped me retain ideas that i’d encountered unexpectedly and left me feeling changed in any way, big or small. this process helped me to keep them in my conscious brain; i could return to them, apply them, and adapt them for regular daily practice, and for thinking about bigger questions about “practice.”

some classical arts practices require as their starting point a malleable body that is not yet fully grown or self-aware. bigger questions arise when that body experiences a moment of reckoning, like a change in physical ability, or the need for a new expressive language. this questioning could also happen through a more emergent process, like the gradual transformation of self-perception, or a changing personal relationship with a dominant cultural practice that has drawn a varied many into its global sweep.

there’s something about violin culture that makes this state of inquiry feel especially acute. there’s an intensity to its pedagogies and practices, its social significance for various groups, and the complex histories implicated in its material and conceptual origination. its hyper-responsiveness and bright tension orients our whole body around it. it reveals things about us (with or without our consent). it poses problems that need solving, makes wounds that need healing. the trope of violin trauma exists in part because violin orthodoxy dictates that we sublimate ourselves to these intensities.

but because we become so physically enmeshed with the instrument in this way, and so invested in its capacity to reflect back something of ourselves, it can also lead us toward discoveries that are profound, generative and healing. i imagined that this aspect of the practice could use a different kind of etude–one in the form of a text piece, movement prompt, or meditation–that might assist in this continual process of inquiry and discovery.

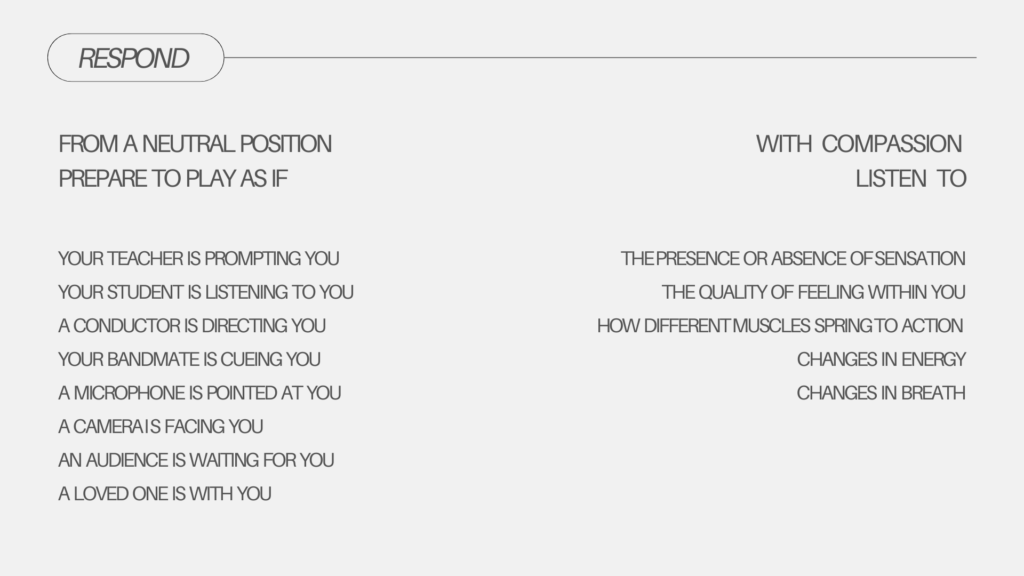

respond

i love the moment our bodies organize to create sound. our internal response to that moment expresses so much about our relationship to ourselves and others, the way the practice shaped us, the way the body keeps adapting. exploring this emergent meaning can feel very vulnerable, but also funny or tender or absurd…

this text etude is inspired by a prompt i loved from a movement course for instrumentalists created by feldenkrais practitioner andrew gibbons.

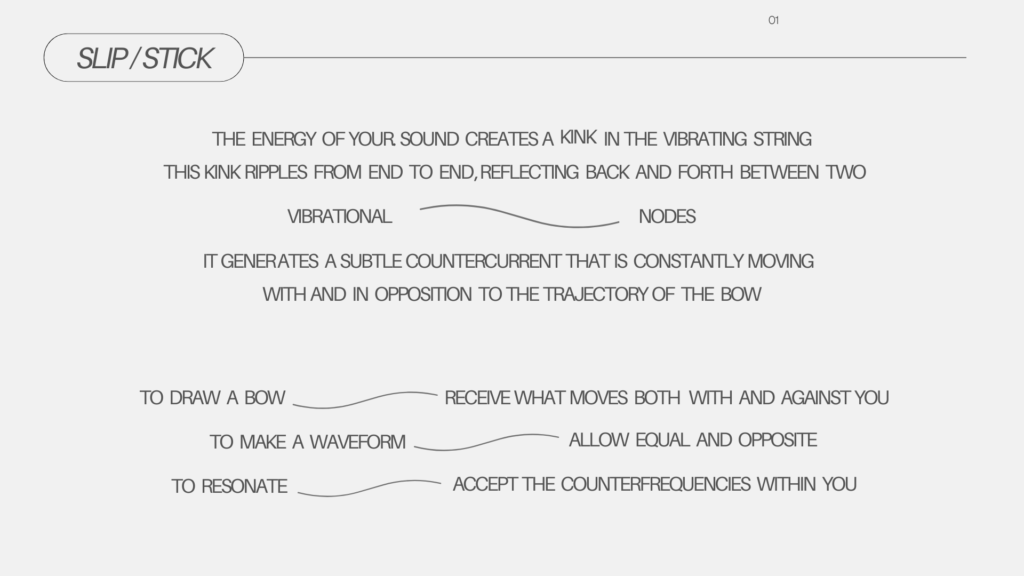

slip/stick

making any sound on the violin is a collaborative effort — the attunement of (at least) two separate universes of capacities, tendencies, preferences. the act of sounding any instrument is also an act of receptivity. we strive to recognize that its independent behaviors are always present, influencing our own thoughts and actions.

i love how the phenomenon of slip/stick reminds me of this dynamic. slip/stick occurs beyond the scope of our sensory perception, but deepening our receptivity allows us to respond to it and to receive and accept our instrument’s ungovernable qualities, along with our own.

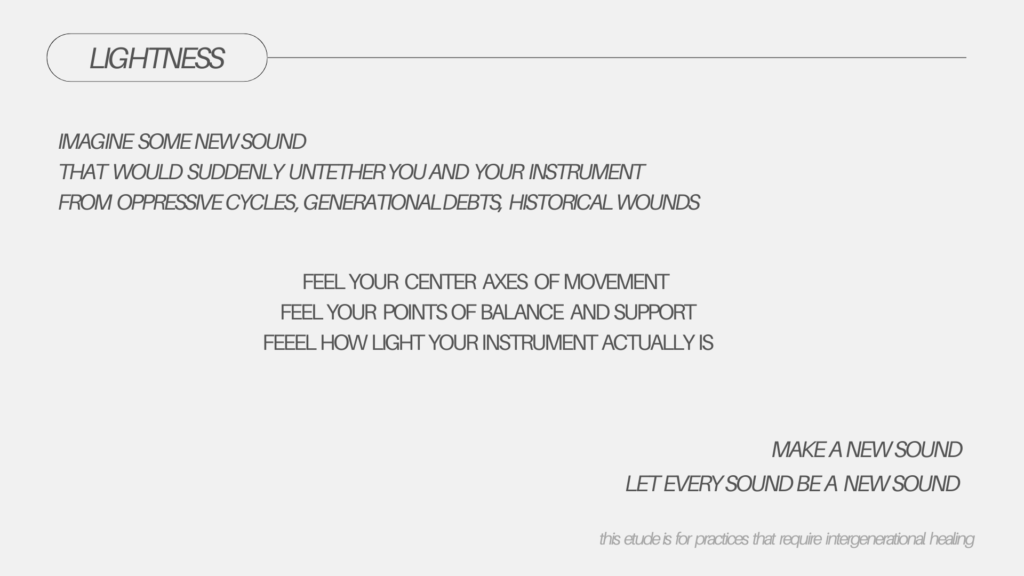

lightness

some instruments are implicated in heavy histories. the intensity of these narratives sometimes draws us into patterns of effort that can turn into harmful cycles. but what if freeing ourselves required little effort? the movement prompt here has helped me rethink effort, and reminds me how shifts in perspective can change the lightness or heaviness of an object, movement, or feeling.

this was inspired by a basic body awareness concepts as well as a line in a poem from the therīgāthā, a text by early buddhist nuns: “if you truly want to be free, make every thought a thought of freedom.”

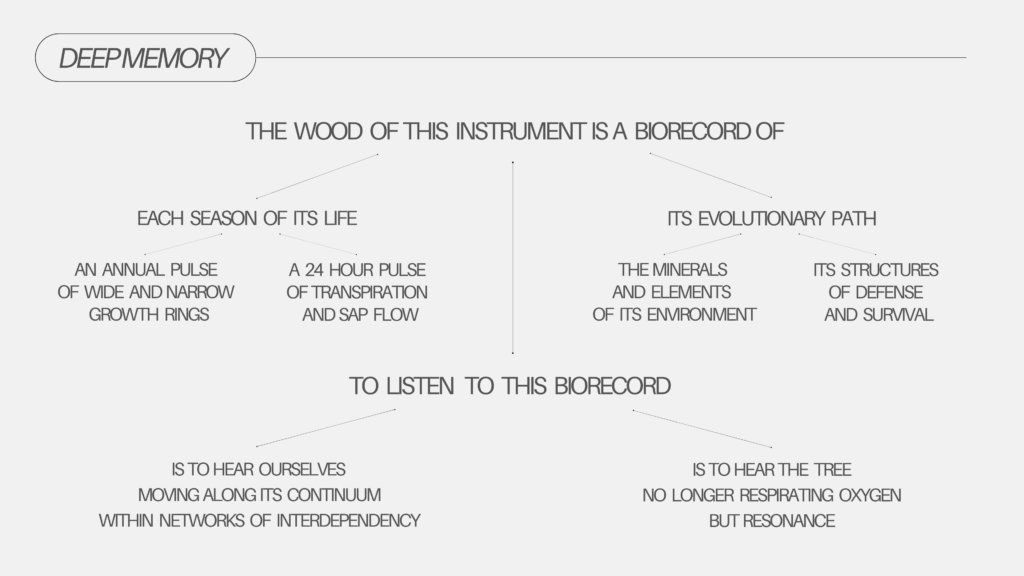

deep memory

because our instruments are made from once-living things (skin, hair, gut, wood, resin) or the elemental materials of the earth (metals, minerals, oils) they have deep memory beyond our own. considering a violin’s arborescent origins means engaging with an arborescent body and biorecord: the memory of its environment during its lifetime, and the evolutionary journey beyond its lifetime. we understand this instrument as an entity independent from us, with a history independent from its current state. what does this mean for practice? for me, it’s a prompt to broaden my perceptual field, and to loosen fixed self-regard: to locate instrument and self within networks of interdependence, and to locate my practice as a moving point on a far-reaching continuum.

this etude is inspired by the writing of biologist david george haskell, and by the work of sculptor giuseppe penone.

spiral

acts of interpretation are acts of creation. illustrating the interpretive process as a branching, wandering spiral helps me visualize it not as linear progress, but as the cyclical, expansive, self-reflexive, generative creative process that it truly is. the results could resemble hand-drawn line topography, or irregular concentric tree rings, or a labyrinth–giving us an additional layer of meaning to weave into the interpretive spaces between text and context.

this etude was inspired by the concept of the “hermeneutic-interpretative spiral” from melissa trimingham’s “a methodology for practice as research.”